Last month, a bunch of Democratic Party leaders and strategists scuttled off to a retreat in Virginia to plan their comeback. Per Politico, this was their advice for Democrats:

“embrace patriotism, community, and traditional American imagery”;

“ban far-left candidate questionnaires and refuse to participate in forums that create ideological purity tests” and “move away from the dominance of small-dollar donors whose preferences may not align with the broader electorate”; and

“push back against far-left staffers and groups that exert a disproportionate influence on policy and messaging.”

The idea that the Democratic Party’s real problem is the visibility of the left within its coalition has a lot of purchase in establishment circles. The argument has grown in popularity as the political fight over transgender rights has intensified. Rahm Emanuel, former Obama Chief of Staff and Chicago mayor, recently said that Democrats are focusing too much on gender identity issues. Various middling pundits have taken the same line.

The gist of the argument coming from the strategist types is simple: left-wing positions, on culture war issues like trans rights especially, are not popular with the broad public, and the party would do well to distance themselves. At a glance, this seems like common sense. In reality, it’s just not how politics work.

Many political strategists imagine that voters hold a handful of heartfelt positions, and that the goal of politicians is to meet them where they are. You find some voters who support gay rights, you find some others who support environmental conservation, you offer them favorable policies, and voila, you’ve got a political coalition brewing. If too many voters come out against one of those issues, you drop it to save your skin and preserve the rest of your coalition.

That is almost entirely backwards. A wealth of research shows that voters don’t come to their policy preferences organically - they follow the cues of political figures they identify with. Meaning that generally speaking, it’s not that politicians see where voters stand and try to move toward them, it’s the other way around.

This sounds unintuitive and almost unbelievable to most people who hear it. Are we all really just moving at the whims of political elites? Am I so fickle?

In the 2000 election between Al Gore and George W. Bush, one of the big issues was Social Security privatization. Bush wanted to (partially) privatize, Gore didn’t. Political scientist Gabriel Lenz looked at survey data gathered from voters both early in the election cycle and then again right before the election. He found that initially, there was little correlation between voters’ positions on Social Security privatization and their choice of candidate. By the time the election rolled around, however, the voters had seemingly sorted themselves: people who supported privatization tended to support Bush, and people who opposed it supported Gore.

You might think this makes sense: people saw what the candidates stood for, and then aligned with the candidate who matched their position. But that’s not what happened. The surveys showed that the voters’ choice of candidates generally hadn’t changed. Instead, they had changed their position on Social Security privatization to match their chosen candidate. Not only that, but almost no voters changed their preferred candidate based on the issue. The voters weren’t switching candidates based on their policy positions, they were switching policy positions based on their candidate.

There are countless studies reaching similar conclusions. “Party cues,” as political scientists call them, are powerful things. It’s been found that party cues have lasting effects, and in some cases can even overcome voters’ own self-interest. Lenz wrote a book on the subject where he compiled and analyzed much of the existing research. He concluded that “instead of politicians following voters on policy, voters appear to follow politicians.”

This idea has its limitations: research shows that the ability of political leaders to influence voters is minimal in some circumstances. When issues are already salient and opinions have hardened, the ability of party leaders to drive opinion wanes. A candidate is not likely to change an affordable housing expert’s position on affordable housing. But for an issue like trans rights, which has only come to the center of the public’s attention recently, voters are highly moveable.

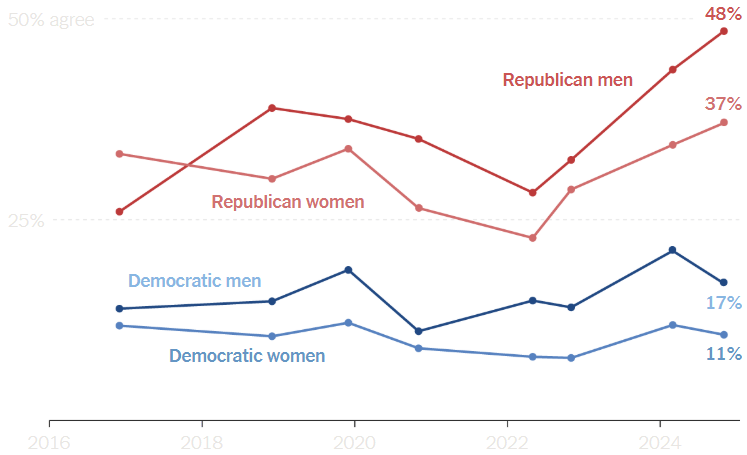

Here is a rather disturbing chart, published last week in The New York Times. The chart measures whether people in either party agree that women should “return to their traditional roles in society”:

Source: NYT; data from the Views of the Electorate Research Survey

The percentage of Republican men who believe that women should return to their traditional roles in society has jumped from 28 to 48%. Among Republican women, the increase is from 23 to 37%. This has happened in the span of two years. As alarming as this is, it’s important to ask yourself: what do you think happened here? Do you think that Republican voters, organically and of their own volition, drastically shifted their fundamental perceptions of women’s role in society? Of course not. They are being influenced by messaging from conservative elites, who themselves are radicalizing on issues of race and gender.

This dynamic is often obvious. YouGov polling shows Republican support for higher tariffs at 51%, with just 5% supporting lower tariffs. A year ago those numbers were 38 and 20%, respectively. Again, what happened? Did they all read the same economics textbook? Or did they follow the lead of Donald Trump, who made higher tariffs a central campaign issue?

Democrats tend to miss this. When Kamala Harris lost, several prominent Democrats said the party had strayed too far from the public on trans issues. Gavin Newsom, speaking on his new podcast to his guest Charlie Kirk (Jesus Christ) repeated the talking point just this week. But just a few years ago the savvy political wisdom was that Republican anti-trans efforts had overstepped, alienating voters. Republicans, though, weren’t cowed by public opinion. Rather than retreat, they went on the offensive, seeking to reshape the public debate. And they did, leveraging inflection points like women’s sports to galvanize their base and push liberals into a defensive posture.

If you’re a political party, your goal is not just to know where voters stand, but to know how to move them. Instead, Democratic operatives seem content to reduce their platform to a focus-grouped ephemera, drifting whichever way the political winds blow it.

The exact reason for this tendency in Democratic politics is hard to pinpoint. It’s partially the result of a party that has always half-believed the smear that it is not the party of “real Americans.” It’s partially the natural output of managing a big tent coalition. And it’s partially the result of the infiltration into the party of a consultant class whose only real value-add is their ability to conduct polls and focus groups in order to craft The Perfect Message.

No matter the cause, the problem for Democrats is existential. The Republican Party and its vast media apparatus are engaged in a campaign to reframe the most fundamental debates about American society: the role of women and minorities in public life, the continued existence of the New Deal state, the contours of the right to vote. If all Democrats do is attempt to match public opinion, they’ll be forever operating within a Republican frame, stuck watching the polls while Republicans move them. What has happened with trans rights will happen over and over; an endless cycle of perpetual retreat.

I don’t mean to reduce the issue to a cold political calculus. The best justification for supporting trans rights is that trans people are real and deserve civil protections. If supporting them was deeply unpopular, it would still be the right thing to do. Politics isn’t a series of McKinsey presentations, it weighs on human life and dignity.

But even by their own terms, the party strategists have it wrong: you can’t win just by abiding the polls. Politics are forged, built on will and leadership. Democrats need to decide whether they want to fight for the things they believe in, or spend the rest of their days chasing polls but never catching them.